Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

Great dialogue is hard to pin down, but you know it when you hear or see it. In the earlier parts of this guide, we showed you some well-known tips and rules for writing dialogue. In this section, we'll show you those rules in action with 15 examples of great dialogue, breaking down exactly why they work so well.

In the opening of Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered, we meet Willa Knox, a middle-aged and newly unemployed writer who has just inherited a ramshackle house.

“The simplest thing would be to tear it down,” the man said. “The house is a shambles.”

She took this news as a blood-rush to the ears: a roar of peasant ancestors with rocks in their fists, facing the evictor. But this man was a contractor. Willa had called him here and she could send him away. She waited out her panic while he stood looking at her shambles, appearing to nurse some satisfaction from his diagnosis. She picked out words.

“It’s not a living thing. You can’t just pronounce it dead. Anything that goes wrong with a structure can be replaced with another structure. Am I right?”

“Correct. What I am saying is that the structure needing to be replaced is all of it. I’m sorry. Your foundation is nonexistent.”

Alfred Hitchcock once described drama as "life with the boring bits cut out." In this passage, Kingsolver cuts out the boring parts of Willa's conversation with her contractor and brings us right to the tensest, most interesting part of the conversation.

By entering their conversation late, the reader is spared every tedious detail of their interaction.

Instead of a blow-by-blow account of their negotiations (what she needs done, when he’s free, how she’ll be paying), we’re dropped right into the emotional heart of the discussion. The novel opens with the narrator learning that the home she cherishes can’t be salvaged.

By starting off in the middle of (relatively obscure) dialogue, it takes a moment for the reader to orient themselves in the story and figure out who is speaking, and what they’re speaking about. This disorientation almost mirrors Willa’s own reaction to the bad news, as her expectations for a new life in her new home are swiftly undermined.

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

In the first piece of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice, we meet Mr and Mrs Bennet, as Mrs Bennet attempts to draw her husband into a conversation about neighborhood gossip.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer.

“Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

This was invitation enough.

“Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

Austen’s dialogue is always witty, subtle, and packed with character. This extract from Pride and Prejudice is a great example of dialogue being used to develop character relationships.

We instantly learn everything we need to know about the dynamic between Mr and Mrs Bennet’s from their first interaction: she’s chatty, and he’s the beleaguered listener who has learned to entertain her idle gossip, if only for his own sake (hence “you want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it”).

There is even a clear difference between the two characters visually on the page: Mr Bennet responds in short sentences, in simple indirect speech, or not at all, but this is “invitation enough” for Mrs Bennet to launch into a rambling and extended response, dominating the conversation in text just as she does audibly.

The fact that Austen manages to imbue her dialogue with so much character-building realism means we hardly notice the amount of crucial plot exposition she has packed in here. This heavily expository dialogue could be a drag to get through, but Austen’s colorful characterization means she slips it under the radar with ease, forwarding both our understanding of these people and the world they live in simultaneously.

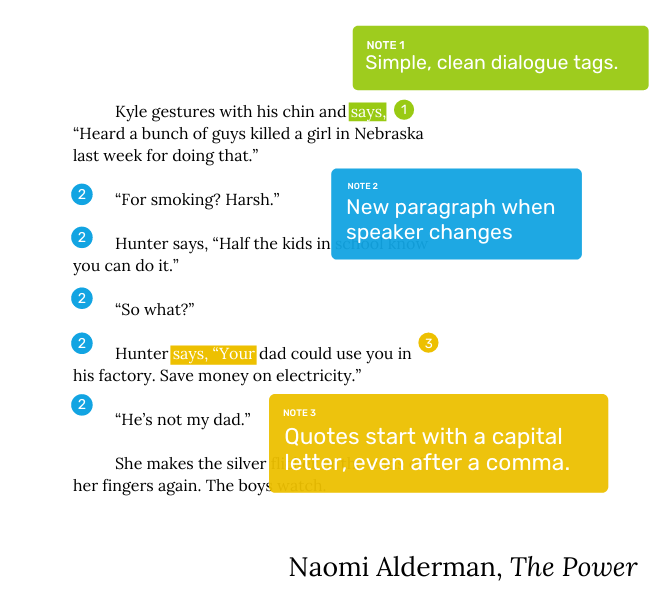

In The Power, young women around the world suddenly find themselves capable of generating and controlling electricity. In this passage, between two boys and a girl who just used those powers to light her cigarette.

Kyle gestures with his chin and says, “Heard a bunch of guys killed a girl in Nebraska last week for doing that.”

“For smoking? Harsh.”

Hunter says, “Half the kids in school know you can do it.”

“So what?”

Hunter says, “Your dad could use you in his factory. Save money on electricity.”

“He’s not my dad.”

She makes the silver flicker at the ends of her fingers again. The boys watch.

Alderman here uses a show, don’t tell approach to expositional dialogue. Within this short exchange, we discover a lot about Allie, her personal circumstances, and the developing situation elsewhere. We learn that women are being punished harshly for their powers; that Allie is expected to be ashamed of those powers and keep them a secret, but doesn’t seem to care to do so; that her father is successful in industry; and that she has a difficult relationship with him. Using dialogue in this way prevents info-dumping backstory all at once, and instead helps us learn about the novel’s world in a natural way.

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

Here, friends Tommy and Kathy have a conversation after Tommy has had a meltdown. After being bullied by a group of boys, he has been stomping around in the mud, the precise reaction they were hoping to evoke from him.

“Tommy,” I said, quite sternly. “There’s mud all over your shirt.”

“So what?” he mumbled. But even as he said this, he looked down and noticed the brown specks, and only just stopped himself crying out in alarm. Then I saw the surprise register on his face that I should know about his feelings for the polo shirt.

“It’s nothing to worry about.” I said, before the silence got humiliating for him. “It’ll come off. If you can’t get it off yourself, just take it to Miss Jody.”

He went on examining his shirt, then said grumpily, “It’s nothing to do with you anyway.”

This episode from Never Let Me Go highlights the power of interspersing action beats within dialogue. These action beats work in several ways to add depth to what would otherwise be a very simple and fairly nondescript exchange. Firstly, they draw attention to the polo shirt, and highlight its potential significance in the plot. Secondly, they help to further define Kathy’s relationship with Tommy.

We learn through Tommy’s surprised reaction that he didn’t think Kathy knew how much he loved his seemingly generic polo shirt. This moment of recognition allows us to see that she cares for him and understands him more deeply than even he realized. Kathy breaking the silence before it can “humiliate” Tommy further emphasizes her consideration for him. While the dialogue alone might make us think Kathy is downplaying his concerns with pragmatic advice, it is the action beats that tell the true story here.

The eponymous hobbit Bilbo is engaged in a game of riddles with the strange creature Gollum.

"What have I got in my pocket?" he said aloud. He was talking to himself, but Gollum thought it was a riddle, and he was frightfully upset.

"Not fair! not fair!" he hissed. "It isn't fair, my precious, is it, to ask us what it's got in its nassty little pocketses?"

Bilbo seeing what had happened and having nothing better to ask stuck to his question. "What have I got in my pocket?" he said louder. "S-s-s-s-s," hissed Gollum. "It must give us three guesseses, my precious, three guesseses."

"Very well! Guess away!" said Bilbo.

"Handses!" said Gollum.

"Wrong," said Bilbo, who had luckily just taken his hand out again. "Guess again!"

"S-s-s-s-s," said Gollum, more upset than ever.

Tolkein’s dialogue for Gollum is a masterclass in creating distinct character voices. By using a repeated catchphrase (“my precious”) and unconventional spelling and grammar to reflect his unusual speech pattern, Tolkien creates an idiosyncratic, unique (and iconic) speech for Gollum. This vivid approach to formatting dialogue, which is almost a transliteration of Gollum's sounds, allows readers to imagine his speech pattern and practically hear it aloud.

We wouldn’t recommend using this extreme level of idiosyncrasy too often in your writing — it can get wearing for readers after a while, and Tolkien deploys it sparingly, as Gollum’s appearances are limited to a handful of scenes. However, you can use Tolkien’s approach as inspiration to create (slightly more subtle) quirks of speech for your own characters.

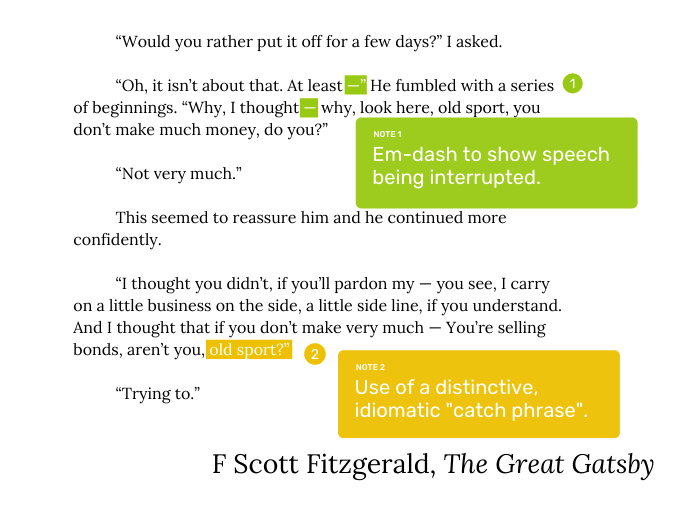

The narrator, Nick has just done his new neighbour Gatsby a favor by inviting his beloved Daisy over to tea. Perhaps in return, Gatsby then attempts to make a shady business proposition.

“There’s another little thing,” he said uncertainly, and hesitated.

“Would you rather put it off for a few days?” I asked.

“Oh, it isn’t about that. At least —” He fumbled with a series of beginnings. “Why, I thought — why, look here, old sport, you don’t make much money, do you?”

“Not very much.”

This seemed to reassure him and he continued more confidently.

“I thought you didn’t, if you’ll pardon my — you see, I carry on a little business on the side, a little side line, if you understand. And I thought that if you don’t make very much — You’re selling bonds, aren’t you, old sport?”

“Trying to.”

This dialogue from The Great Gatsby is a great example of how to make dialogue sound natural. Gatsby tripping over his own words (even interrupting himself, as marked by the em-dashes) not only makes his nerves and awkwardness palpable but also mimics real speech. Just as real people often falter and make false starts when they’re speaking off the cuff, Gatsby too flounders, giving us insight into his self-doubt; his speech isn’t polished and perfect, and neither is he despite all his efforts to appear so.

Fitzgerald also creates a distinctive voice for Gatsby by littering his speech with the character's signature term of endearment, “old sport”. We don’t even really need dialogue markers to know who’s speaking here — a sign of very strong characterization through dialogue.

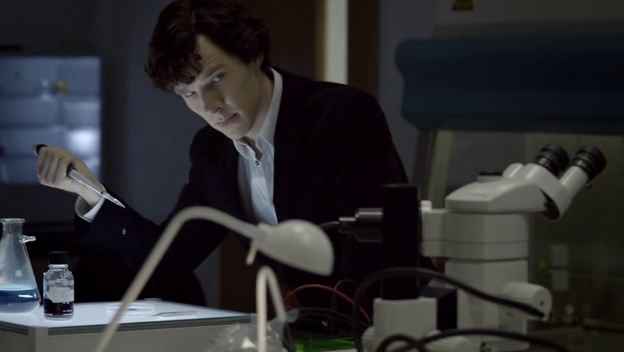

In this first meeting between the two heroes of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, John is introduced to Sherlock while the latter is hard at work in the lab.

“How are you?” he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for which I should hardly have given him credit. “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.”

“How on earth did you know that?” I asked in astonishment.

“Never mind,” said he, chuckling to himself. “The question now is about hemoglobin. No doubt you see the significance of this discovery of mine?”

“It is interesting, chemically, no doubt,” I answered, “but practically— ”

“Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years. Don’t you see that it gives us an infallible test for blood stains. Come over here now!” He seized me by the coat-sleeve in his eagerness, and drew me over to the table at which he had been working. “Let us have some fresh blood,” he said, digging a long bodkin into his finger, and drawing off the resulting drop of blood in a chemical pipette. “Now, I add this small quantity of blood to a litre of water. You perceive that the resulting mixture has the appearance of pure water. The proportion of blood cannot be more than one in a million. I have no doubt, however, that we shall be able to obtain the characteristic reaction.” As he spoke, he threw into the vessel a few white crystals, and then added some drops of a transparent fluid. In an instant the contents assumed a dull mahogany colour, and a brownish dust was precipitated to the bottom of the glass jar.

“Ha! ha!” he cried, clapping his hands, and looking as delighted as a child with a new toy. “What do you think of that?”

This passage uses a number of the key techniques for writing naturalistic and exciting dialogue, including characters speaking over one another and the interspersal of action beats.

Sherlock cutting off Watson to launch into a monologue about his blood experiment shows immediately where Sherlock’s interest lies — not in small talk, or the person he is speaking to, but in his own pursuits, just like earlier in the conversation when he refuses to explain anything to John and is instead self-absorbedly “chuckling to himself”. This helps establish their initial rapport (or lack thereof) very quickly.

Breaking up that monologue with snippets of him undertaking the forensic tests allows us to experience the full force of his enthusiasm over it without having to read an uninterrupted speech about the ins and outs of a science experiment.

Starting to think you might like to read some Sherlock? Check out our guide to the Sherlock Holmes canon!

Here, our protagonist Wallace is questioned by Ramon, a friend-of-a-friend, over the fact that he is considering leaving his PhD program.

Wallace hums. “I mean, I wouldn’t say that I want to leave, but I’ve thought about it, sure.”

“Why would you do that? I mean, the prospects for… black people, you know?”

“What are the prospects for black people?” Wallace asks, though he knows he will be considered the aggressor for this question.

Brandon Taylor’s Real Life is drawn from the author’s own experiences as a queer Black man, attempting to navigate the unwelcoming world of academia, navigating the world of academia, and so it’s no surprise that his dialogue rings so true to life — it’s one of the reasons the novel is one of our picks for must-read books by Black authors.

This episode is part of a pattern where Wallace is casually cornered and questioned by people who never question for a moment whether they have the right to ambush him or criticize his choices. The use of indirect dialogue at the end shows us this is a well-trodden path for Wallace: he has had this same conversation several times, and can pre-empt the exact outcome.

This scene is also a great example of the dramatic significance of people choosing not to speak. The exchange happens in front of a big group, but — despite their apparent discomfort — nobody speaks up to defend Wallace, or to criticize Ramon’s patronizing microaggressions. Their silence is deafening, and we get a glimpse of Ramon’s isolation due to the complacency of others, all due to what is not said in this dialogue example.

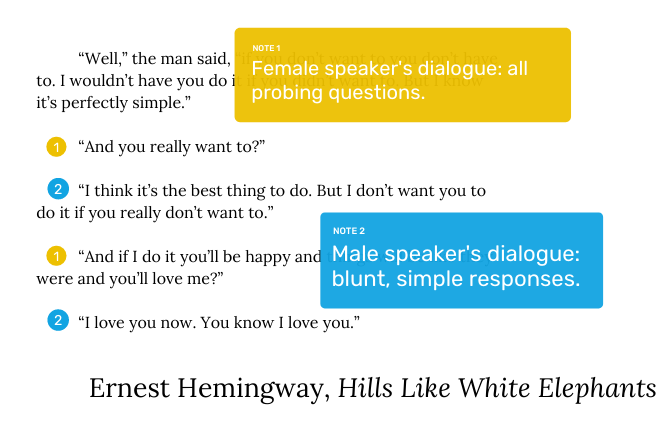

In this short story, an unnamed man and a young woman discuss whether or not they should terminate a pregnancy while sitting on a train platform.

“Well,” the man said, “if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.”

“And you really want to?”

“I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you really don’t want to.”

“And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?”

“I love you now. You know I love you.”

“I know. But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?”

“I’ll love it. I love it now but I just can’t think about it. You know how I get when I worry.”

“If I do it you won’t ever worry?”

“I won’t worry about that because it’s perfectly simple.”

This example of dialogue from Hemingway’s short story Hills Like White Elephants moves at quite a clip. The conversation quickly bounces back and forth between the speakers, and the call-and-response format of the woman asking and the man answering is effective because it establishes a clear dynamic between the two speakers: the woman is the one seeking reassurance and trying to understand the man’s feelings, while he is the one who is ultimately in control of the situation.

Note the sparing use of dialogue markers: this minimalist approach keeps the dialogue brisk, and we can still easily understand who is who due to the use of a new paragraph when the speaker changes.

Like this classic author’s style? Head over to our selection of the 11 best Ernest Hemingway books.

In Madeline Miller’s retelling of Greek myth, we witness a conversation between the mythical enchantress Circe and Telemachus (son of Odysseus).

“You do not grieve for your father?”

“I do. I grieve that I never met the father everyone told me I had.”

I narrowed my eyes. “Explain.”

“I am no storyteller.”

“I am not asking for a story. You have come to my island. You owe me truth.”

A moment passed, and then he nodded. “You will have it.”

This short and punchy exchange hits on a lot of the stylistic points we’ve covered so far. The conversation is a taut tennis match between the two speakers as they volley back and forth with short but impactful sentences, and unnecessary dialogue tags have been shaved off. It also highlights Circe’s imperious attitude, a result of her divine status. Her use of short, snappy declaratives and imperatives demonstrates that she’s used to getting her own way and feels no need to mince her words.

This is an early conversation between seventeen-year-old Elio and his family’s handsome new student lodger, Oliver.

What did one do around here? Nothing. Wait for summer to end. What did one do in the winter, then?

I smiled at the answer I was about to give. He got the gist and said, “Don’t tell me: wait for summer to come, right?”

I liked having my mind read. He’d pick up on dinner drudgery sooner than those before him.

“Actually, in the winter the place gets very gray and dark. We come for Christmas. Otherwise it’s a ghost town.”

“And what else do you do here at Christmas besides roast chestnuts and drink eggnog?”

He was teasing. I offered the same smile as before. He understood, said nothing, we laughed.

He asked what I did. I played tennis. Swam. Went out at night. Jogged. Transcribed music. Read.

He said he jogged too. Early in the morning. Where did one jog around here? Along the promenade, mostly. I could show him if he wanted.

It hit me in the face just when I was starting to like him again: “Later, maybe.”

Dialogue is one of the most crucial aspects of writing romance — what’s a literary relationship without some flirty lines? Here, however, Aciman gives us a great example of efficient dialogue. By removing unnecessary dialogue and instead summarizing with narration, he’s able to confer the gist of the conversation without slowing down the pace unnecessarily. Instead, the emphasis is left on what’s unsaid, the developing romantic subtext.

Furthermore, the fact that we receive this scene in half-reported snippets rather than as an uninterrupted transcript emphasizes the fact that this is Elio’s own recollection of the story, as the manipulation of the dialogue in this way serves to mimic the nostalgic haziness of memory.

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

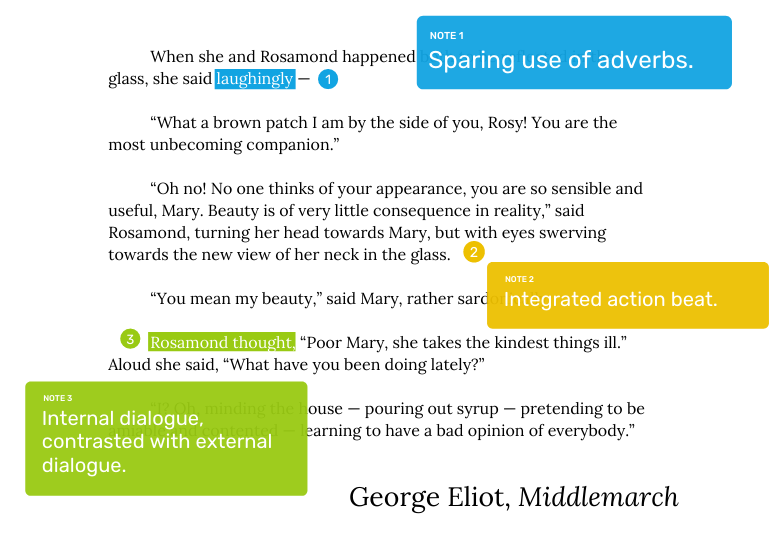

Two of Eliot’s characters, Mary and Rosamond, are out shopping,

When she and Rosamond happened both to be reflected in the glass, she said laughingly —

“What a brown patch I am by the side of you, Rosy! You are the most unbecoming companion.”

“Oh no! No one thinks of your appearance, you are so sensible and useful, Mary. Beauty is of very little consequence in reality,” said Rosamond, turning her head towards Mary, but with eyes swerving towards the new view of her neck in the glass.

“You mean my beauty,” said Mary, rather sardonically.

Rosamond thought, “Poor Mary, she takes the kindest things ill.” Aloud she said, “What have you been doing lately?”

“I? Oh, minding the house — pouring out syrup — pretending to be amiable and contented — learning to have a bad opinion of everybody.”

This excerpt, a conversation between the level-headed Mary and vain Rosamond, is an example of dialogue that develops character relationships naturally. Action descriptors allow us to understand what is really happening in the conversation.

Whilst the speech alone might lead us to believe Rosamond is honestly (if clumsily) engaging with her friend, the description of her simultaneously gazing at herself in a mirror gives us insight not only into her vanity, but also into the fact that she is not really engaged in her conversation with Mary at all.

The use of internal dialogue cut into the conversation (here formatted with quotation marks rather than the usual italics) lets us know what Rosamond is actually thinking, and the contrast between this and what she says aloud is telling. The fact that we know she privately realizes she has offended Mary, but quickly continues the conversation rather than apologizing, is emphatic of her character. We get to know Rosamond very well within this short passage, which is a hallmark of effective character-driven dialogue.

Here, Mary (speaking first) reacts to her husband Ethan’s attempts to discuss his previous experiences as a disciplined soldier, his struggles in subsequent life, and his feeling of impending change.

“You’re trying to tell me something.”

“Sadly enough, I am. And it sounds in my ears like an apology. I hope it is not.”

“I’m going to set out lunch.”

Steinbeck’s Winter of our Discontent is an acute study of alienation and miscommunication, and this exchange exemplifies the ways in which characters can fail to communicate, even when they’re speaking. The pair speaking here are trapped in a dysfunctional marriage which leaves Ethan feeling isolated, and part of his loneliness comes from the accumulation of exchanges such as this one. Whenever he tries to communicate meaningfully with his wife, she shuts the conversation down with a complete non sequitur.

We expect Mary’s “you’re trying to tell me something” to be followed by a revelation, but Ethan is not forthcoming in his response, and Mary then exits the conversation entirely. Nothing is communicated, and the jarring and frustrating effect of having our expectations subverted goes a long way in mirroring Ethan’s own frustration.

Just like Ethan and Mary, we receive no emotional pay-off, and this passage of characters talking past one another doesn’t further the plot as we hope it might, but instead gives us insight into the extent of these characters’ estrangement.

The disillusioned main character of Bret Easton Ellis’ debut novel, Clay, here catches up with a college friend, Daniel, whom he hasn’t seen in a while.

He keeps rubbing his mouth and when I realize that he’s not going to answer me, I ask him what he’s been doing.

“Been doing?”

“Yeah.”

“Hanging out.”

“Hanging out where?”

“Where? Around.”

Less Than Zero is an elegy to conversation, and this dialogue is an example of the many vacuous exchanges the protagonist engages in, seemingly just to fill time. The whole book is deliberately unpoetic and flat, and depicts the lives of disaffected youths in 1980s LA. Their misguided attempts to fill the emptiness within them with drink and drugs are ultimately fruitless, and it shows in their conversations: in truth, they have nothing to say to one another at all.

This utterly meaningless exchange would elsewhere be considered dead weight to a story. Here, rather than being fat in need of trimming, the empty conversation is instead thematically resonant.

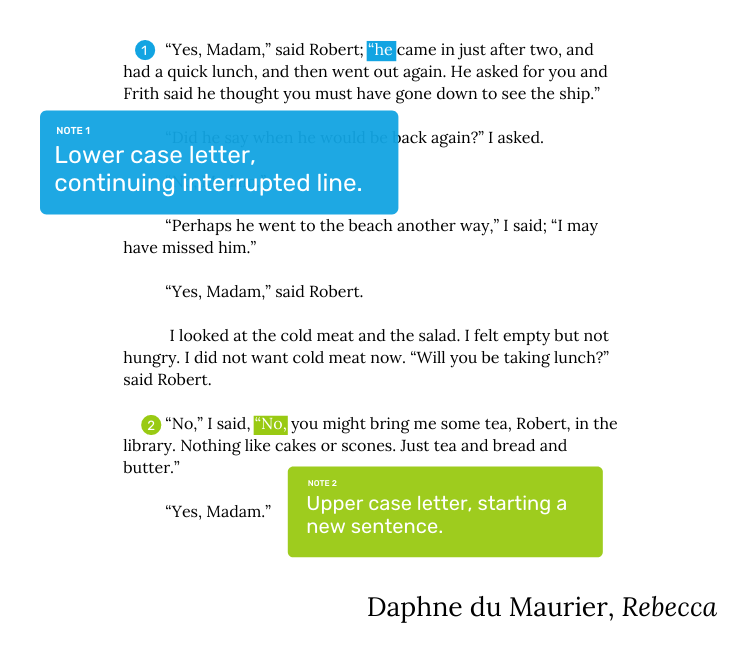

The young narrator of du Maurier’s classic gothic novel here has a strained conversation with Robert, one of the young staff members at her new husband’s home, the unwelcoming Manderley.

“Has Mr. de Winter been in?” I said.

“Yes, Madam,” said Robert; “he came in just after two, and had a quick lunch, and then went out again. He asked for you and Frith said he thought you must have gone down to see the ship.”

“Did he say when he would be back again?” I asked.

“No, Madam.”

“Perhaps he went to the beach another way,” I said; “I may have missed him.”

“Yes, Madam,” said Robert.

I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now. “Will you be taking lunch?” said Robert.

“No,” I said, “No, you might bring me some tea, Robert, in the library. Nothing like cakes or scones. Just tea and bread and butter.”

“Yes, Madam.”

We’re including this one in our dialogue examples list to show you the power of everything Du Maurier doesn’t do: rather than cycling through a ton of fancy synonyms for “said”, she opts for spare dialogue and tags.

This interaction's cold, sparse tone complements the lack of warmth the protagonist feels in the moment depicted here. By keeping the dialogue tags simple, the author ratchets up the tension — without any distracting flourishes taking the reader out of the scene. The subtext of the conversation is able to simmer under the surface, and we aren’t beaten over the head with any stage direction extras.

The inclusion of three sentences of internal dialogue in the middle of the dialogue (“I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now.”) is also a masterful touch. What could have been a single sentence is stretched into three, creating a massive pregnant pause before Robert continues speaking, without having to explicitly signpost one. Manipulating the pace of dialogue in this way and manufacturing meaningful silence is a great way of adding depth to a scene.

Phew! We've been through a lot of dialogue, from first meetings to idle chit-chat to confrontations, and we hope these dialogue examples have been helpful in illustrating some of the most common techniques.

If you’re looking for more pointers on creating believable and effective dialogue, be sure to check out our course on writing dialogue. Or, if you find you learn better through examples, you can look at our list of 100 books to read before you die — it’s packed full of expert storytellers who’ve honed the art of dialogue.

– Originally published on Jan 14, 2021

Previous post in series