is represented by an arrow." />

is represented by an arrow." />The genetic information stored in DNA is a living archive of instructions that cells use to accomplish the functions of life. Inside each cell, catalysts seek out the appropriate information from this archive and use it to build new proteins — proteins that make up the structures of the cell, run the biochemical reactions in the cell, and are sometimes manufactured for export. Although all of the cells that make up a multicellular organism contain identical genetic information, functionally different cells within the organism use different sets of catalysts to express only specific portions of these instructions to accomplish the functions of life.

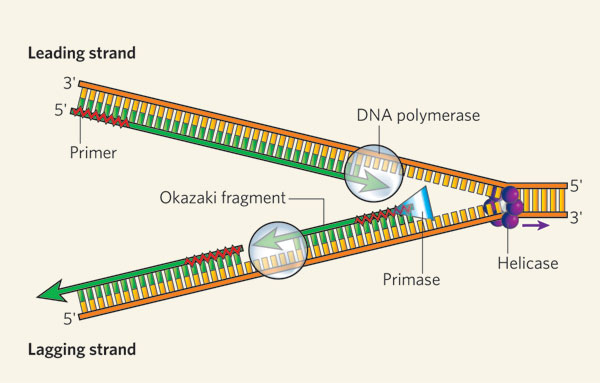

When a cell divides, it creates one copy of its genetic information — in the form of DNA molecules — for each of the two resulting daughter cells. The accuracy of these copies determines the health and inherited features of the nascent cells, so it is essential that the process of DNA replication be as accurate as possible (Figure 1).

is represented by an arrow." />

is represented by an arrow." />

The helicase unzips the double-stranded DNA for replication, making a forked structure. The primase generates short strands of RNA that bind to the single-stranded DNA to initiate DNA synthesis by the DNA polymerase. This enzyme can work only in the 5' to 3' direction, so it replicates the leading strand continuously. Lagging-strand replication is discontinuous, with short Okazaki fragments being formed and later linked together.

![]()

© 2006 Nature Publishing Group Bell, S. D. Molecular biology: Prime-time progress. Nature 439, 542-543 (2006). All rights reserved.

One factor that helps ensure precise replication is the double-helical structure of DNA itself. In particular, the two strands of the DNA double helix are made up of combinations of molecules called nucleotides. DNA is constructed from just four different nucleotides — adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G) — each of which is named for the nitrogenous base it contains. Moreover, the nucleotides that form one strand of the DNA double helix always bond with the nucleotides in the other strand according to a pattern known as complementary base-pairing — specifically, A always pairs with T, and C always pairs with G (Figure 2). Thus, during cell division, the paired strands unravel and each strand serves as the template for synthesis of a new complementary strand.

![]()

© 2009 Nature Education All rights reserved.

In most multicellular organisms, every cell carries the same DNA, but this genetic information is used in varying ways by different types of cells. In other words, what a cell "does" within an organism dictates which of its genes are expressed. Nerve cells, for example, synthesize an abundance of chemicals called neurotransmitters, which they use to send messages to other cells, whereas muscle cells load themselves with the protein-based filaments necessary for muscle contractions.

RNA polymerase (green) synthesizes a strand of RNA that is complementary to the DNA template strand below it.

![]()

© 2009 Nature Education All rights reserved.

Transcription is the first step in decoding a cell's genetic information. During transcription, enzymes called RNA polymerases build RNA molecules that are complementary to a portion of one strand of the DNA double helix (Figure 3).

RNA molecules differ from DNA molecules in several important ways: They are single stranded rather than double stranded; their sugar component is a ribose rather than a deoxyribose; and they include uracil (U) nucleotides rather than thymine (T) nucleotides (Figure 4). Also, because they are single strands, RNA molecules don't form helices; rather, they fold into complex structures that are stabilized by internal complementary base-pairing.

is represented by a different color. Where a red-colored nucleotide appears on the DNA molecule, a yellow nucleotide appears on the RNA molecule (thus there are no red nucleotides on the RNA molecule)." />

is represented by a different color. Where a red-colored nucleotide appears on the DNA molecule, a yellow nucleotide appears on the RNA molecule (thus there are no red nucleotides on the RNA molecule)." />

![]()

© 2009 Nature Education All rights reserved.

Three general classes of RNA molecules are involved in expressing the genes encoded within a cell's DNA. Messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules carry the coding sequences for protein synthesis and are called transcripts; ribosomal RNA (rRNA) molecules form the core of a cell's ribosomes (the structures in which protein synthesis takes place); and transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules carry amino acids to the ribosomes during protein synthesis. In eukaryotic cells, each class of RNA has its own polymerase, whereas in prokaryotic cells, a single RNA polymerase synthesizes the different class of RNA. Other types of RNA also exist but are not as well understood, although they appear to play regulatory roles in gene expression and also be involved in protection against invading viruses.

mRNA is the most variable class of RNA, and there are literally thousands of different mRNA molecules present in a cell at any given time. Some mRNA molecules are abundant, numbering in the hundreds or thousands, as is often true of transcripts encoding structural proteins. Other mRNAs are quite rare, with perhaps only a single copy present, as is sometimes the case for transcripts that encode signaling proteins. mRNAs also vary in how long-lived they are. In eukaryotes, transcripts for structural proteins may remain intact for over ten hours, whereas transcripts for signaling proteins may be degraded in less than ten minutes.

Cells can be characterized by the spectrum of mRNA molecules present within them; this spectrum is called the transcriptome. Whereas each cell in a multicellular organism carries the same DNA or genome, its transcriptome varies widely according to cell type and function. For instance, the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas contain transcripts for insulin, but bone cells do not. Even though bone cells carry the gene for insulin, this gene is not transcribed. Therefore, the transcriptome functions as a kind of catalog of all of the genes that are being expressed in a cell at a particular point in time.

This Escherichia coli cell has been treated with chemicals and sectioned so its DNA and ribosomes are clearly visible. The DNA appears as swirls in the center of the cell, and the ribosomes appear as dark particles at the cell periphery.

![]()

Courtesy of Dr. Abraham Minsky (2014). All rights reserved.

Ribosomes are the sites in a cell in which protein synthesis takes place. Cells have many ribosomes, and the exact number depends on how active a particular cell is in synthesizing proteins. For example, rapidly growing cells usually have a large number of ribosomes (Figure 5).

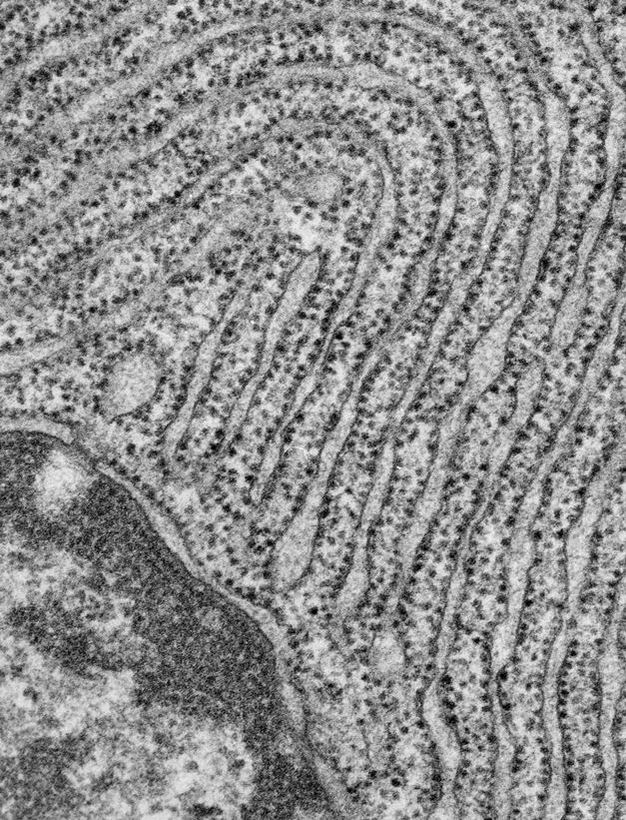

Ribosomes are complexes of rRNA molecules and proteins, and they can be observed in electron micrographs of cells. Sometimes, ribosomes are visible as clusters, called polyribosomes. In eukaryotes (but not in prokaryotes), some of the ribosomes are attached to internal membranes, where they synthesize the proteins that will later reside in those membranes, or are destined for secretion (Figure 6). Although only a few rRNA molecules are present in each ribosome, these molecules make up about half of the ribosomal mass. The remaining mass consists of a number of proteins — nearly 60 in prokaryotic cells and over 80 in eukaryotic cells.

Within the ribosome, the rRNA molecules direct the catalytic steps of protein synthesis — the stitching together of amino acids to make a protein molecule. In fact, rRNA is sometimes called a ribozyme or catalytic RNA to reflect this function.

Eukaryotic and prokaryotic ribosomes are different from each other as a result of divergent evolution. These differences are exploited by antibiotics, which are designed to inhibit the prokaryotic ribosomes of infectious bacteria without affecting eukaryotic ribosomes, thereby not interfering with the cells of the sick host.

Electron micrograph of a pancreatic exocrine cell section. The cytosol is filled with closely packed sheets of endoplasmic reticulum membrane studded with ribosomes. At the bottom left is a portion of the nucleus and its nuclear envelope. Image courtesy of Prof. L. Orci (University of Geneva, Switzerland).

![]()

© 2014 Nature Publishing Group Schekman, R. Merging cultures in the study of membrane traffic. Nature Cell Biology 6, 483-486 (2004) doi:10.1038/ncb0604-483. All rights reserved.